The Beaux-Arts interior of the Palace Theater is a protected landmark, so developers had to devise a plan to raise it three stories in their effort to add more retail space.

By C. J. Hughes

Photographs by Jeenah Moon

May 28, 2022

If you’ve ever lost at Jenga by toppling a tower after removing a block, you might appreciate what developers have accomplished at TSX Broadway, a hotel and entertainment complex in Times Square.

The developer of the 46-story building has managed to loosen its bottom floors and lift them 30 feet without sending anything crashing down to earth.

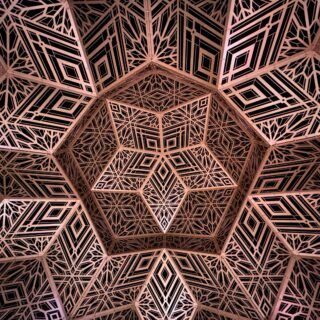

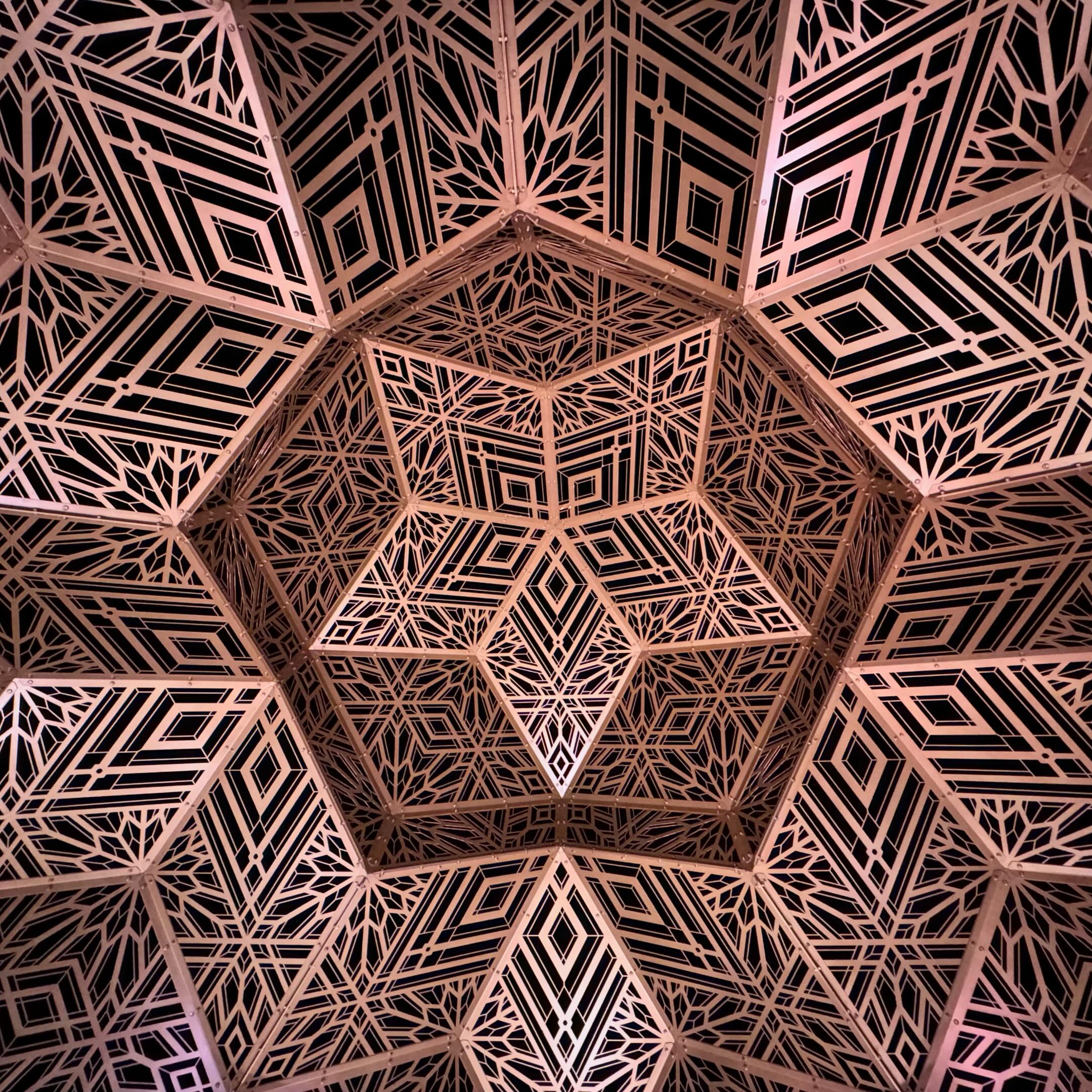

And what has been elevated is not just any old section. It’s the Palace Theater, a home for Broadway shows that was designed by the architectural firm Kirchhoff & Rose in the Beaux-Arts style. The theater, which weighs 14 million pounds, is a protected landmark, meaning the structure, from the stage to the balcony, had to be moved without suffering as much as a crack in the delicate plasterwork adorning ceilings, arches and box seats.

“It’s been quite a feeling to see it happen,” said Anthony J. Mazzo, the president of Urban Foundation/Engineering, which accomplished the heavy lift using a system of jacks and telescoping beams that he invented 30 years ago for a project involving a warehouse roof in Queens. “I feel like it’s worked like a charm,” he added.

Even in a city known for outsize construction feats, the project was full of risks, from possible damage to the ornate interior to the chance that the entire theater would crash to the ground. But it was a crucial part of a $2.5 billion transformation of the building, which will include a 661-room hotel and an outdoor stage facing Times Square when it opens next year.

Since 1913, the 1,700-seat Palace occupied the bulk of the ground floor at West 47th Street and Broadway, drawing hundreds of visitors eight times a week to see musicals like “Annie,” “Sunset Boulevard” and “West Side Story.” But offering only live theater was choking off an even bigger source of revenue: the tens of millions of tourists who swarm Times Square in a typical year, eager to spend money in stores.

Annual retail rents in Times Square, close to $2,000 per square foot, are typically among the nation’s highest. The pandemic depressed the area, which drew just 35,000 visitors a day on weekends in spring 2020. But two years later, that number has climbed to 300,000, according to the Times Square Alliance, a coalition that works to improve and promote the district.

Daily business updates The latest coverage of business, markets and the economy, sent by email each weekday.

To tap some of that potential revenue, L&L Holding, the lead developer on the TSX project, made arrangements with the theater’s owner, the Nederlander Organization, to elevate the Palace and fill the void with three floors of new shopping space, part of 10 floors of retail in the tower. The theater will have a new entrance on West 47th as well as a new lobby, marquee and backstage area.

“It was critical for us to lift the theater to create the space, but also to unlock the potential of the theater, with all the things that would help it become a modern building,” said David Orowitz, an L&L managing director.

Urban Foundation had a playbook to follow. In 1998, it rolled the Beaux-Arts Empire Theater on West 42nd Street 170 feet west as part of a plan by the developer Forest City Ratner to make way for stores. Today, the building is the 25-screen AMC Empire movie theater with a twinkling marquee.

But at 7.4 million pounds, the Empire was half the Palace’s weight. Besides, the tracks used to move the Empire were basically sunk into the ground beneath it, meaning the building had to be raised only a few inches, said Mr. Mazzo, who was also the engineer on that project.

Anybody who has ever changed a car tire by using a strategically placed jack or frame rack might be familiar with how the Palace made its upward journey.

A crew of three dozen workers first strengthened the theater by adding a six-foot-thick concrete layer around the edge of the base, then sank 34 columns 30 feet into the Manhattan bedrock beneath it. Fitting snugly into the columns, like hands in gloves, were smaller beams that could move up and down like telescope parts. Four hydraulic jacks resembling large paint cans with arms that extended up were placed under collars on each beam.

When the jacks were turned on, they pushed the collars up, and the theater with them. After the jacks’ arms were raised a mere five inches, workers stopped the lift, secured the theater at its new height, adjusted the collars and fastened them with large bolts, repositioned the jacks and restarted the whole process.

In March, when the Palace had cleared 16 feet, the lift project was paused so workers could construct new floors in the freshly made space, which also helped to support the theater.

Throughout the process, a handful of people huddled in a plywood shack with their eyes on monitors installed in the theater. A slight tilt less than half a degree one way or another would have been enough for a hard stop, said Robert Israel, an executive vice president of L&L who worked on the TSX project.

Further complicating the delicate nature of lifting a 7,000-ton theater, many aspects of the TSX project have overlapped since work began in 2019, including demolition of the old Doubletree Hotel above the theater and the construction of its replacement, the pouring of a new foundation and the addition of 51,000 square feet of signage on the building’s exterior.

Also, zoning codes have changed since the tower was added in the late 1980s, which could have meant a significant reduction in square footage for the final product. But under current New York zoning law, if a renovation project keeps a quarter of its floor space in place, it can preserve its original square footage.

To ensure that TSX Broadway maintained its size — about 500,000 square feet — L&L had to retain many of the existing concrete slabs from the 16th story on down, essentially keeping them suspended in the air while construction proceeded around them in another Jenga-like feat.

“This is by far the most complex project that I have ever undertaken, that L&L has undertaken,” Mr. Israel said as he stood in a dim, cool space beneath the Palace, which bore construction notes scrawled in spray paint that theatergoers will never see.

The theater reached its final height on April 5, an accomplishment that was celebrated a month later with a media event that included city officials, L&L executives and Broadway producers.

One of Broadway’s oldest theaters, the Palace had undergone changes before. In 1926, its owner installed an “electric piano in its lobby to compete with the popular nearby Roxy,” according to the 1987 report from the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission that led to protected status for much of the theater’s interior. But the lobby, which was made over in the 1930s, in the 1960s and again in the 1980s, never received landmark status and was demolished as part of the TSX overhaul.

Functioning primarily as a movie theater for RKO Pictures for the middle of the 20th century, the Palace was also home to acts like Harry Houdini, Diana Ross and Judy Garland, who completed a 19-week run in 1951 and ’52. The Nederlander family bought the theater in 1965 and gave it a $500,000 makeover, after which it began hosting Broadway musicals, beginning with the premiere of Neil Simon’s “Sweet Charity.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

Now, as the theater prepares to welcome visitors once more, it is seen as a proxy for the rebound of Times Square and New York.

“We were symbolic of the pause in the pandemic, and we are symbolic of the resolve of the recovery,” said Tom Harris, the president of the Times Square Alliance.